When the turtles

come marching in

Every year around the month of March, the shore line at certain beaches in Odisha begins to look slightly different. An increasing number of olive ridley turtles are seen congregating in the offshore waters waiting for the right cues to start nesting. Taking signals from their surroundings, these turtles emerge from the sea and start climbing the beach at Gahirmatha and Rushikulya, to lay their eggs. For a lot of these turtles it’s been a whole year since they’ve stepped on land. For some it’s been more.

The event, known as an arribada (in Spanish meaning arrival), is one of the largest mass nesting events of ridleys globally. Over 100,000 female ridleys lay nests over a span of three or four days. Mass nesting is a survival strategy, thought to overwhelm predators and ensure that a sufficient number of eggs are left behind to hatch. The Kemp’s ridley is the only other species of marine turtle known to exhibit mass nesting behaviour.

Temperature Sex Determination

In sea turtles, the sex of a hatchling depends on the temperature it is exposed to during incubation. Eggs exposed to warmer temperatures produce females, while males emerge from eggs exposed to lower temperatures. Sea turtle clutches are often entirely male or female depending on whether they are laid during the warmer or cooler part of the year, or sometimes even on the kind of beach.

Sea turtles are able to maintain sex ratios by nesting at different times of the year or on different beaches. With temperatures on the rise due to climate change, sex ratios may become skewed towards females, which may threaten the stability of these populations.

A Race for Survival

Turtle eggs take about two months to incubate. Once a hatchling is ready to leave its shell, it uses a little tooth at the top of its beak to break through the leathery shell of its egg. After breaking open its shell, the hatchling absorbs the remaining yolk sac and waits for its siblings to break open their shells as well. This stage is critical for a hatchling to survive the next phase of their life. It takes three to four days for hatchlings to break out of their shells and they emerge from the nest almost in unison to increase their chances of survival.

For a defenseless hatchling, the warm offshore waters provide security and getting to it is their first milestone. In the race against time to avoid both land and water predators, hatchlings emerge from nests at night in a state referred to as a juvenile frenzy and instinctively trace a frantic course to the shoreline, which they identify by the reflection of the moon and starlight on the water. Of every thousand hatchlings that make it to sea, only one is believed to survive to adulthood.

LOST YEARS

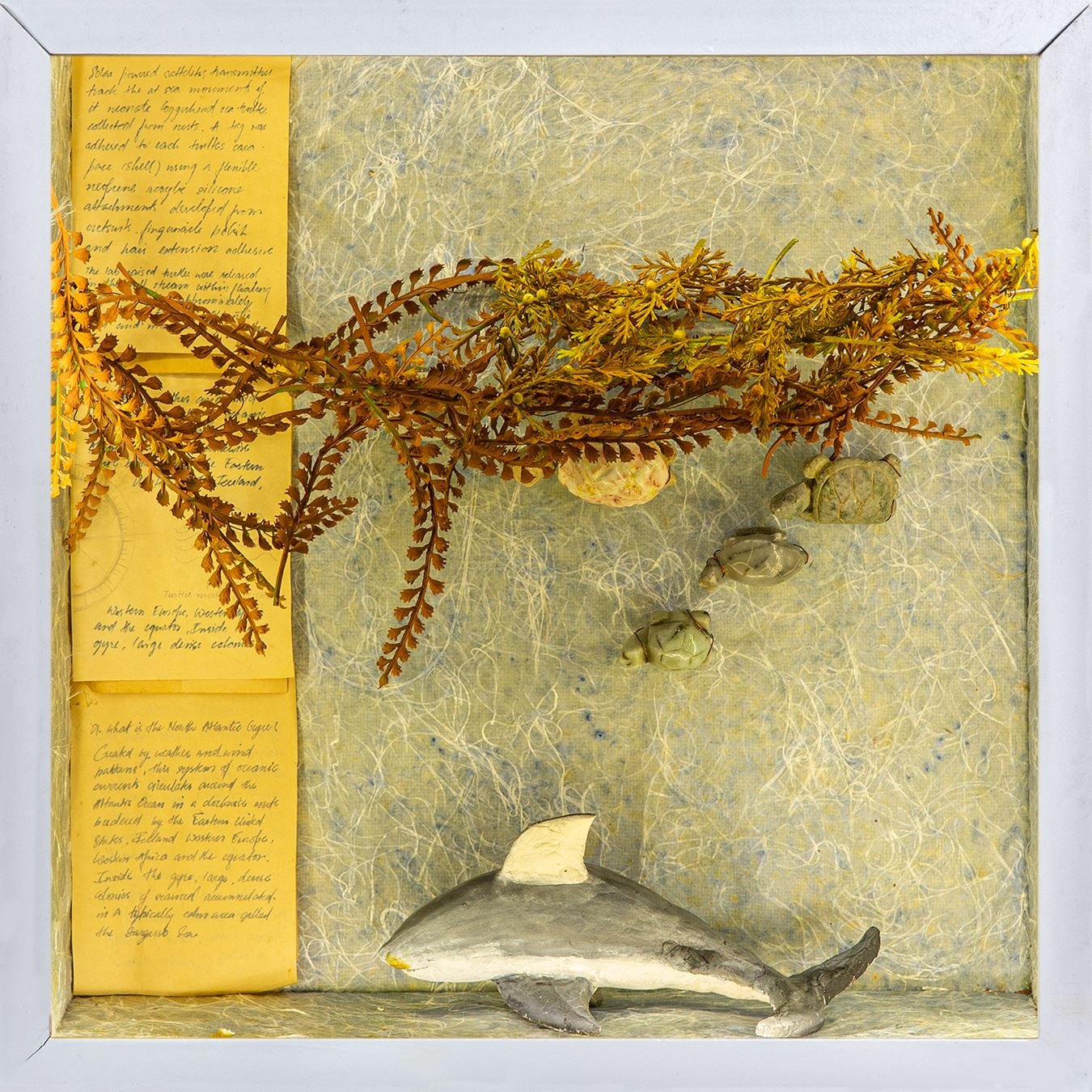

For several decades, the time between a hatchling heading to sea and reaching their juvenile feeding ground remained a mystery to biologists. This phase of their lives was therefore referred to as the lost years. Recent research and fieldwork has been able to shed some light on this period of their lives.

Hatchlings spend the first few days of their lives swimming out into the open ocean to escape from seabirds and large fish, like sharks. Sustained by the yolk sac from the egg, hatchlings are able to swim for a few days without having to eat. These hatchlings find refuge in drifting seaweed islands, where they feed on plants, snails, small crabs, barnacles and shrimp. Hatchlings spend many years drifting across entire ocean basins on currents and gyres before they are old enough to move to their juvenile feeding grounds.

THERE AND BACK AGAIN

A female turtle returns to nest in the region she herself hatched; sometimes even to the same beach. This is known as natal homing. Sea turtles are often referred to as mariners of the sea, for their incredible ability to navigate the vast oceans using information that gets imprinted when they are young.

For instance, olive ridley turtles in India travel from their feeding grounds in Sri Lanka all the way up to Odisha to nest. Like other migratory animals, turtles may have an iron crystal in their brain, called magnetite, which they use to sense the earth’s magnetic fields. Hatchlings, which first sense direction when emerging from the nest based on visual cues, orient themselves to the earth’s magnetic field during the rapid crawl to the shoreline. This instinct later helps them navigate their way to feeding and breeding grounds, and in the case of female turtles, back to their nesting beaches.

TURTLE DIETS:

BALANCING MARINE FOOD WEBS

As juveniles, most sea turtles are omnivores but adults have specific diet preferences that play an important role in ocean ecosystems. Leatherbacks get their nutritional needs from small, gelatinous jellyfish and can consume up to 400 pounds per day. They regulate jellyfish populations that would otherwise feed on fish eggs and larvae. Loggerheads, during their early developmental stage feed on small animals living in floating mats of algae (sargassum). However, juveniles and adults largely feed on bottom-dwelling invertebrates, horseshoe crabs and sea urchins, using their powerful jaws designed to crush their prey. Hawksbill are amongst the only spongivorous vertebrates. While many sponges are toxic, their body fats absorb the toxins without making them ill but this makes hawksbill meat potentially poisonous for humans. Sponges compete aggressively for space with reef-building corals.

By removing sponges from reefs, hawksbills allow other species, such as coral, to colonize and grow. Both olive ridleys and Kemp’s ridleys are omnivorous and feed on crabs, mollusks, shrimp, fish and jellyfish. Green turtles are one of the very few remaining marine herbivores that eat seagrass. The decline of green turtles can result in a loss of productivity in the food web, including commercially exploited reef fish.

The threats they face

Sea turtles face numerous threats throughout their life cycle that can be either land or sea based. Their struggle for survival against natural predators, like, dogs, crows, crabs and ants begins as hatchlings and continues to their adulthood, against large marine predators like sharks.

Human induced threats such as poaching or harvesting of eggs for consumption and illegal trading of shells have reduced over time but still exist. At sea, thousands of sea turtles accidentally get entangled in operational fishing nets or ghost gear and the numbers are hard to quantify. There is also a high degree of sea turtle mortality by ingestion of plastics that end up in ocean, mostly from storm drains and rivers. Fibropapillomatosis, a widespread disease among turtles has been associated with marine pollution from agricultural, chemical or industrial runoffs, fertilizers or oil spills. In addition, infrastructure development, coastal armoring, beach erosion and tourism have disturbed their nesting habitats.

The second avatar of Vishnu

In Hindu mythology, turtles have been revered as an incarnation of Vishnu, one of the gods of the Hindu ‘trinity’. The ‘Kurma avatar’, named after the sanskrit word for turtles, supported the mountain during the churning of the ocean by the gods and the demons. A mountain was placed on top of the turtle and a snake used as a rope to churn. The churning of the ocean produced divine nectar which the gods and and demons fought over and was ultimately swindled from the demons by Vishnu disguised as a beautiful woman. The avatar symbolises stability amidst opposing forces.

There is even a temple dedicated to the Kurma avatar at Srikurmam near Srikakulam on the Andhra Pradesh coast. Though mythology is unclear on this point, one might argue that the turtle must have been a marine turtle; furthermore, it must have been an olive ridley, given that only ridleys nest at Srikakulam, and in such large numbers at the nearby mass-nesting rookeries in Odisha.

Turtle rhymes from ancient times*

Kumizhi Gnāzhalār Nappasalaiyar (Tamil Sangam literature, circa 4th century ad)

The laying turtle collects and brings a bundle of Ipomea creepers

Keeps them beside the heap of white sand to conceal

Eggs, white as elephant tusks and round and foul smelling

With open mouth, the male awaits the hatching of the young ones

Our fascination with marine turtles is not new; human cultures have interacted with them for tens of thousands of years. One of the earliest known written records of marine turtles from India is a remarkable short poem from Tamil Sangam literature (circa 4th century AD). This is a poetic and near accurate description of a nesting turtle, ‘eggs, white as elephant tusks . . .barring the crocodilian behaviour of the male.’

In sea turtles, there is no parental care, and neither parent awaits the hatching of the young ones, with open mouth or otherwise. Along the southern Indian coast, olive ridleys do, however, often nest in Ipomea (the goat’s foot creeper with pink flowers), though it is far more likely that they are dragging the creepers by chance rather than intent.

*Text from From Soup to Superstar: The Story of Sea Turtle Conservation along the Indian Coast.

Published by Harper Collins Publishers, 2015.

Humans and turtles over millennia*

Sea turtles have been exploited over many centuries, probably millennia, for their meat, shell and eggs. Jack Frazier, a prolific writer and pioneer of sea turtle biology and conservation, finds that sea turtles are known from various archaeological sites in the Middle East from 5000 BCE onwards. Marine turtle remains have been recovered from numerous sites in the Arab world and are also known from the south-eastern US, Caribbean Islands, and Yucatan peninsula. Tortoiseshell products are known from various parts of the world from ancient times, including those from India and Sri Lanka.

Some of the oldest texts referring to marine turtles and their trade are also from several thousand years ago. There are accounts of turtles inscribed on cuneiform tablets from Sumerian cities from about 2000 BCE. Texts from Mesopotamia imply that marine turtles were used for medicine, food and in rituals. There are pictograms of turtles in Chinese writing. In ancient Greece, some authors wrote about the ‘turtle eaters’ (chelonophagi) who were apparently a primitive group of people who lived on islands in the Red Sea and caught and ate the large turtles that were found in their waters.

*Text from From Soup to Superstar: The Story of Sea Turtle Conservation along the Indian Coast.

Published by Harper Collins Publishers, 2015.

Of turtles and pigs

The earliest references to sea turtles in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are in the accounts of British administrators, naturalists, and sociologists from the 1800s. Many of them write accounts of turtle hunting by various tribes.

One of them was Edward Horace Man, who arrived in Port Blair in 1869, and spent the rest of his life working on the islands, occupying various positions including that of Chief Commissioner. Man described the separation between the turtle hunters living on the coast and the pig-hunters of the interior amongst the Andamanese. Among the Ongee of Little Andaman as well, the availability of food is represented by the pig and the turtle from the forest and marine realms respectively.

Recent work suggests that it may have had a role in the Andamanese ethnoanemological belief of playing hide and seek with spirits based on the aroma of foods eaten and foods of the spirit world. Turtle eggs were sometimes eaten raw and the blood was also consumed, after being boiled in the shell till it was thick. Generally, turtles were not consumed during mourning. The importance of sea turtles in Andamanese culture is evident from the fact that the surviving Andamanese still sing turtle hunting songs.

The blood of the turtle*

Turtle fishery at Tuticorin continued despite the introduction of the The Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 and the protection of sea turtles. Once dominated by green turtles, by the 2000s, catches were dominated by olive ridleys with greens forming less than 20 per cent of the fishery. Turtle slaughter was mostly clandestine and the fishermen were wary of sharing information with strangers.

At one point in the 1980s, local youth had formed an association called the Young Christians Blood Drinkers Association as a protest against the protection measures. In 1982, after a survey of the area along with B.C. Choudhury and Anne Ahimaz, Zai Whitaker wrote in The Indian Magazine:

Fresh turtle blood was being drunk as an elixir at one rupee a glass and old men and women gulp it down, blood at the corners of their mouths like so many draculas.

*Text from From Soup to Superstar: The Story of Sea Turtle Conservation along the Indian Coast.

Published by Harper Collins Publishers, 2015.

So excellent a fishe

Named after the Spanish sea captain Juan de Bermúdez, who is the first known European to have visited the archipelago in 1505, Bermuda served as a replenishing point for several ships sailing to the Americas. In 1620, The House of Assembly, the only house in the Bermuda Parliament then, passed its first legislation. In the legislation was an ‘‘Act agynst the killing of ouer young tortoyses”. This law is possibly the first conservation law passed in the “New World”. The law prohibited the killing of young turtles within five leagues of the islands, and the penalty for the offence was fifteen pounds of tobacco, to be shared between the public and the informer.

Several accounts of explorers of the New World mention turtles. They were popular as food amongst these explorers as the turtles could remain alive in their ships for weeks and provided fresh and nutritious meals for the shipmates.

Archie Carr, one of the founding fathers of sea turtle biology and conservation, wrote of his work in the Carribean shores in his book, So Excellent a Fishe, a phrase taken from the Bermuda Assembly Statement.

The ‘valuable natives’ of Tenessarim*

In 1857, following the Indian mutiny (or the first war of Independence, as it is now known), Frederic John Mouat, a British surgeon posted with the Indian Medical Service, was asked to investigate the possibility of the Andaman Islands as a penal colony. Colonel Robert Hyde Colebrook, the Surveyor General of Bengal, surveyed the islands and wrote an account published in 1795. Mouat wrote:

The manuscript account of Colebrooke’s survey is diversified by many light and amusing details. In the course of his voyage, the vessel visited the Diamond Island, lying near the Tenessarim coast, which have always been remarkable for the number of turtles frequenting their shores, offering valuable prizes to the adventurous mariner . . . In the short period of three days, Colonel Colebrooke’s crew secured no fewer than one hundred and two of those valuable natives of the Eastern seas.

According to him, a single turtle had enough meat to feed the ship’s company of a hundred and eighty-five men for a day. With reluctance, they left behind another fifty or sixty turtles that they could easily have captured, but did not have space for.

*Text from From Soup to Superstar: The Story of Sea Turtle Conservation along the Indian Coast.

Published by Harper Collins Publishers, 2015.

A tale of tagged turtles*

Several accounts from the nineteenth century deal with sea turtles in Sri Lanka. For example, there is a remarkable description of how the animals were tagged with brass rings during the Dutch occupation in the late eighteenth century by a district officer to check if descaled hawksbill sea turtles visited the same cove for nesting again. A hawksbill turtle tagged in 1794 was recaptured in 1826 and brought to J.W. Bennett, a member of the Ceylon administration.

The ‘400 pound’ turtle had apparently revisited the same cove to nest for thirty-two years. Ideas about site fidelity in sea turtles existed even at that time. James Emerson Tennant, who was an Irish politician and spent some years as the colonial secretary of Ceylon, said:

In illustration of the resistless influence of instinct at the period of breeding, it may be mentioned that the same tortoise is believed to return again and again to the same spot notwithstanding that at each visit she had to undergo a repetition of this torture.

*Text from From Soup to Superstar: The Story of Sea Turtle Conservation along the Indian Coast.

Published by Harper Collins Publishers, 2015.

Fishing for turtles in Odisha*

Prior to the 1970s, there was no organized fishery for adult turtles in Odisha, but whenever live adult sea turtles were found in fishing nets, they were collected and transported to the nearest railway station from where they were booked to Kolkata. The late 1970s saw heavy directed take of olive ridley turtles in Odisha, fuelled by demand in West Bengal and recently introduced mechanisation in boats. Thousands of turtles were shipped from the coast of Odisha to Kolkata, piled high on their backs in the open coaches of goods trains.

Sea turtle conservation in Odisha began in the early 1970s when the large-scale legal/incidental take of turtles from Gahirmatha was widely reported. In the early 1980s, numerous petitions and letter writing campaigns were supported and endorsed through the Marine Turtle Newsletter, an international newsletter, and several hundred letters were written to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. With increasing pressure from conservationists, the trade declined due to enforcement of laws by the Indian Navy, Indian Coast Guard and the Forest Department of Odisha.

*Text from From Soup to Superstar: The Story of Sea Turtle Conservation along the Indian Coast.

Published by Harper Collins Publishers, 2015.

Local Conservation Action

No single group of humans interacts more closely with turtles than those who share their living spaces with them – coastal communities. Besides identifying these creatures as part of folklore, religious beliefs and cultural practices, coastal communities recognize the role of turtles in contributing to their livelihood.

Coastal communities, especially youth groups, across coastal states of India are coming forth to join hands in protecting nesting grounds, managing marine debris and plastics, reducing fishing-related mortality, and maintaining hatcheries. Conservation efforts which started with thatched huts doubling up as nurseries for hatchlings have often gone on to address related issues such as sustainable fishing and habitat management. These locally-led conservation efforts are very important for securing the future of turtles and their habitats.

A Model of Conservation:

Costa Rica

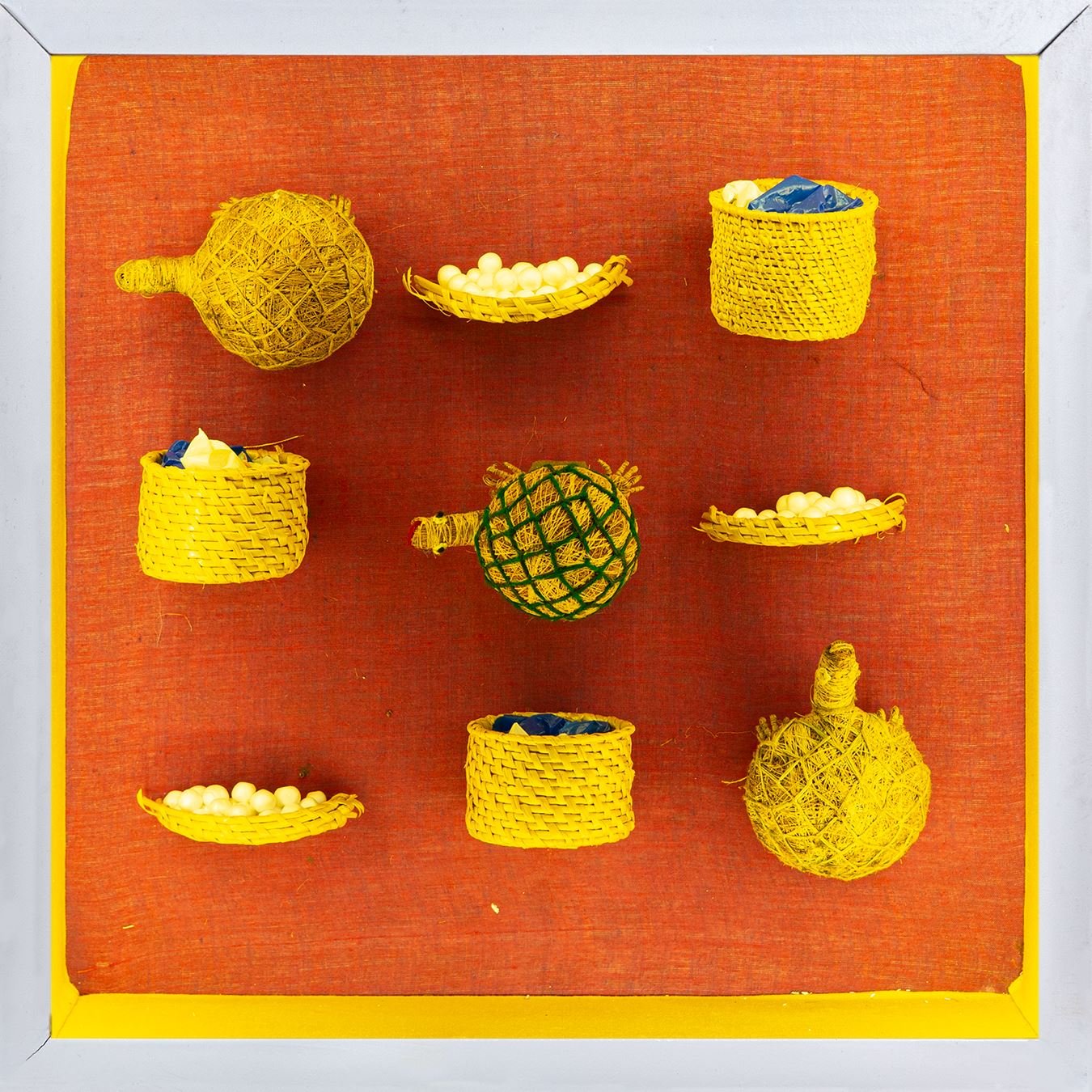

The common practice with sea turtle conservation has been to closely monitor nesting beaches and strictly protect nests from harvest or any human pressures. However, Ostional in north-west Costa Rica has witnessed a different approach to conservation. Here, the local community is allowed to harvest olive ridley turtle eggs on the first two and a half days of the arribada for consumption and sale in the local markets. Eggs deposited during the initial nights of the arribada are destroyed by turtles which nest later. In exchange, the community is responsible for protecting both the nesting beaches and the olive ridley turtles.

The harvest of eggs was fully legalized in 1987, generating income for the community and protecting olive ridley nesting assemblages. Unlike India, where mass nesting occurs once a year, turtles nest all year round at Ostional and nest enmasse once every month for three to five days at the beach. Ostional is a great example of community-driven sustainable use of natural resources.

Turtle Walks:

An Initiation to Conservation

“Turtle Walks” were started by a group of nature enthusiasts from a small beach in Chennai during the 1970s after fishermen reported several instances of turtle nesting.

Having established that nesting begins from December or January, long stretches of nesting beaches were patrolled to locate nests, protect eggs and dissuade poachers. These student groups have also been instrumental in maintaining hatcheries and driving conservation awareness among the communities they work with for over 30 years now.

Over the years, several of these students have gone on to become marine biologists, herpetologists and conservation practitioners.

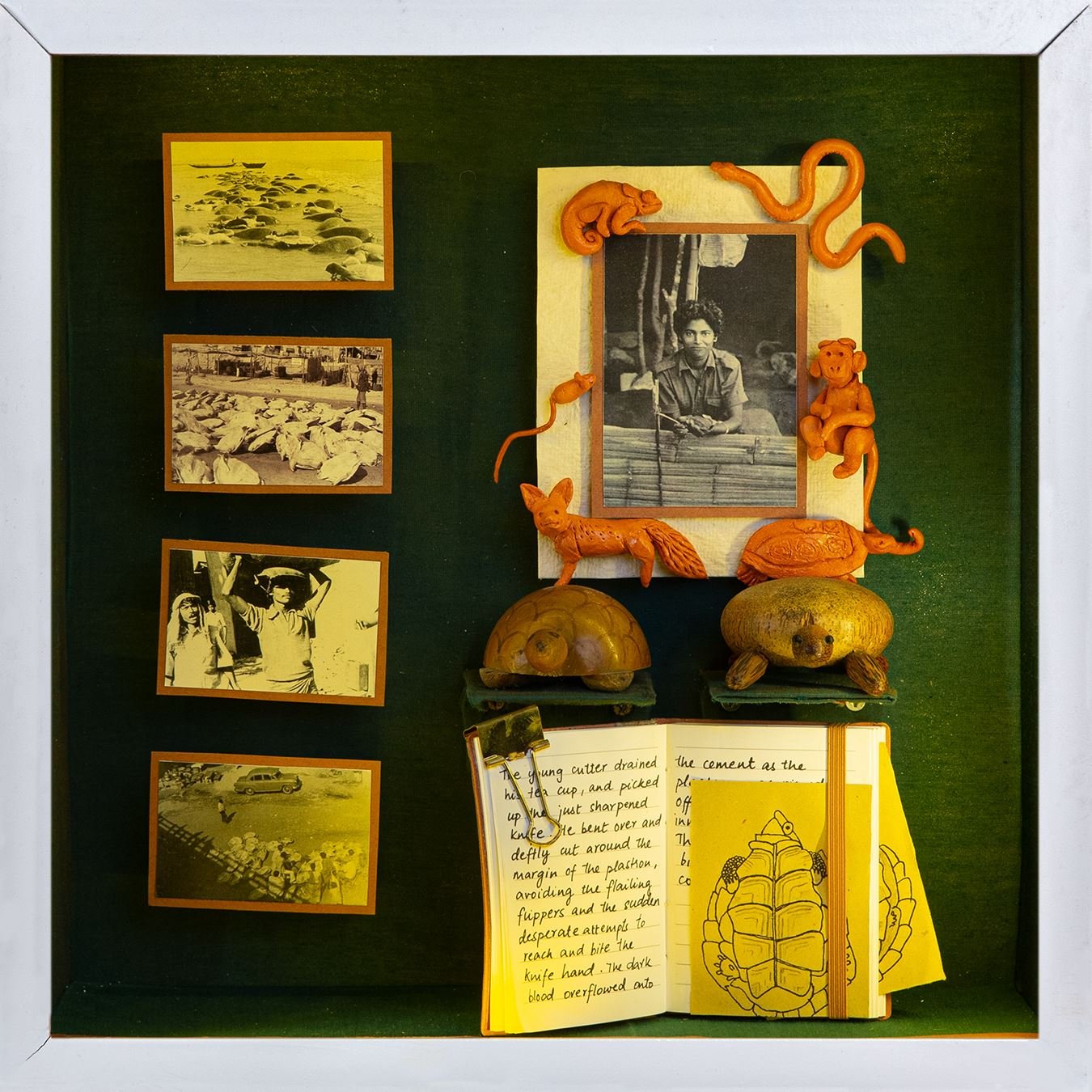

Solitary sojourns in search of turtles

Satish Bhaskar is a pioneer of sea turtle biology and conservation in India. He conducted the first surveys of sea turtles in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the Lakshadweep, among other places. Bhaskar worked with the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust and walked most of India’s entire coastline, more than 4,000 km, looking for sea turtles, their tracks and nests. He also conducted the first leatherback surveys of West Papua in Indonesia. His published and unpublished reports have formed the basis for current sea turtle conservation initiatives.

On his travels, many of which were in remote islands in the Andamans and Nicobars, he had close encounters sharks, dugongs, manta rays, scorpions, and even wild elephants. Travelling with very limited supplies of drinking water, ration and plenty of biscuits, Bhaskar was often marooned and incommunicado on his solitary sojourns. However, he did once manage to set off a message in a bottle from Suheli, an uninhabited island in the Lakshadweep, where he camped alone for 5 months. The bottle reached a fisherman in Sri Lanka, Anthony Damacious, who mailed the letter to Bhaskar’s wife Brenda with a note, a picture of his family and an invitation to Sri Lanka.

The woman with a mission

Conservation, like most professions in the world, has been male-dominated. J. Vijaya, India’s first female herpetologist, created a legacy for herself in this space during her short life. She worked on lizards, snakes, tortoises and turtles in various parts of India. During one of her surveys, she reported on the large numbers of olive ridley turtles being landed in Digha with photographs of hundreds of turtle carcasses (which were later published in India Today). This media attention led the then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, to involve the Odisha Coast Guard in protecting olive ridleys in Odisha, which helped drastically reduce the direct take.

One of her most significant contributions was the rediscovery of the forest cane turtle after 67 years of its being first recorded. In 1984, Vijaya went to the US to Eastern Illinois University to pursue graduate studies. She returned to India for her fieldwork in 1987, and was found dead in a forest. In 2006, the species that she had rediscovered was named after her as Vijayachelys silvatica.

She was a trailblazer among women associated with sea turtle conservation, which includes Anne Ahimaz, Zahida Whitaker, Anne Wright, Belinda Wright and Manjula Tiwari.

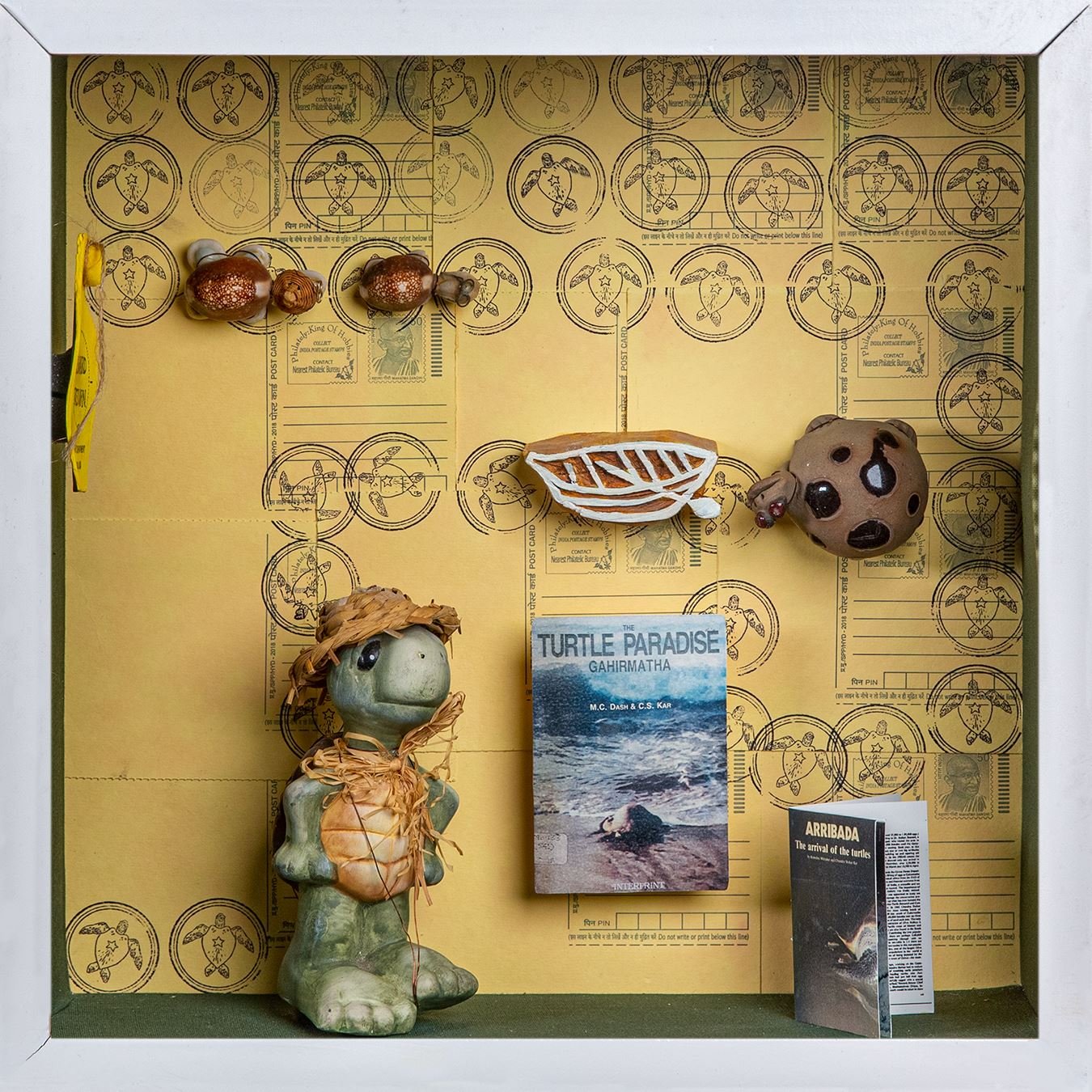

The turtle man of Odisha

Chandrasekhar Kar joined the Forest Department in Odisha as a Research Scholar in 1976 and went on to do pioneering research on olive ridley turtles. He completed his PhD on marine turtles under Robert Bustard who was credited with discovering the rookery at Gahirmatha. Chandrasekhar conducted field work at Gahirmatha between 1977 and 1982, tagging over 10,000 nesting females and amassing huge amounts of data on their nesting biology. Kar’s book, co-authored with his supervisor M.C. Dash, Gahirmatha: A Turtle Paradise is a detailed account of sea turtles in the region and his work there.

Chandrasekhar worked under extremely taxing conditions for several years. His paper with Satish Bhaskar in the ‘Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles’ (1982) remains a classic and comprehensive account of sea turtles in India. Chandrasekhar also discovered a second rookery at the Devi River Mouth in 1981, and along with Bivash Pandav, a third rookery at Rushikulya. He was involved with several research projects on olive ridley turtles in Odisha in the 1990s and 2000s. In 2001, when the very first satellite telemetry project on olive ridley turtles was launched in India, the first turtle fitted with a transmitter was named ‘Chandra’ in his honour.

Finding Rushikulya

Major mass-nesting beaches for olive ridleys around the world are found in Pacific Costa Rica, Mexico and Odisha—making it an extremely rare phenomenon. While solitary nesting occurs along much of the mainland coast of India, the major mass-nesting beaches are in Odisha, notably Gahirmatha and Rushikulya, where more than hundred thousand turtles are known to nest in a single arribada.

As a researcher working with BC Choudhury at the Wildlife Institute of India, Bivash Pandav undertook a survey of the entire coast of Odisha. He was guided by Chandrasekhar Kar who had discovered the second rookery in Odisha at Devi River mouth a decade ago, while the first, Gahirmatha, was discovered by Robert Bustard in the 1970s. Pandav had only a bicycle and food money as support from the Institute. Pandav and Kar met a local fishermen called Damburu who told them that many nesting turtles had been spotted at the mouth of the Rushikulya river. In March 1993, they received a postcard from Damburu. Rushing there, they found that the beach was covered with predated nests and eggshells, and realized they had found another mass nesting site. A couple of months later, they returned to witness mass hatching to confirm their finding.

Surviving the tsunami

Much of the research on sea turtles would not be possible without the able contribution of field assistants. They help researchers collect data, get oriented in field locations and manage field bases that make it possible for researchers to work on their projects. Many of the field assistants working on sea turtle conservation have provided crucial support for decades with many members of their families and communities also joining in.

Saw Agu, a field assistant from the local Karen community with the Andaman and Nicobar Environment Team (ANET), has been working on the sea turtle projects since the late 1990s. In 2004, when the devastating tsunami struck the Indian Ocean, Agu was in remote the Galathea base camp with a young researcher, Ambika Tripathy and four others. Saw Agu was the only one from the base camp who survived. Washed out to sea, he was marooned alone on a log for nearly two weeks without food, water or clothes, and then swam back to shore despite several broken bones. Agu continues to work with ANET, and he and his brother Saw Thesoro have been instrumental in supporting leatherback research in the islands. Their work has shown that, like Agu, the leatherbacks survived the tsunami.